Kris De Decker of Low-Tech Magazine kindly allowed me to republish an article from 2010 – The velomobile: high-tech bike or low-tech car? It gives and an excellent, but slightly dated, overview of the velomobile with a somewhat American flavour. As such the opinions expressed, especially those in the conclusion, are those of the original author. It is none-the-less well worth reading. Here it is largely unedited.

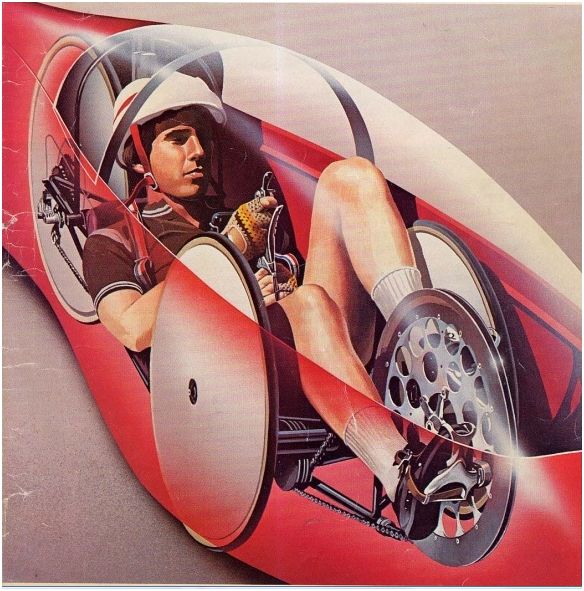

Picture: the Versatile.

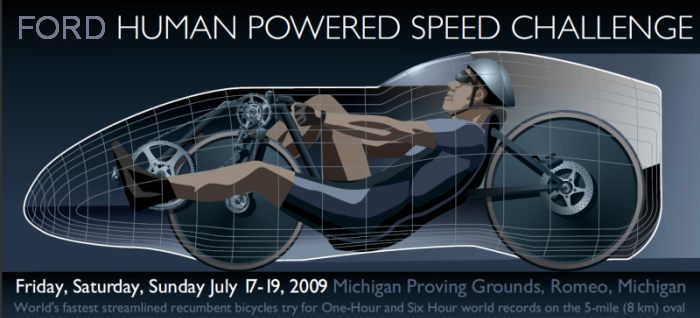

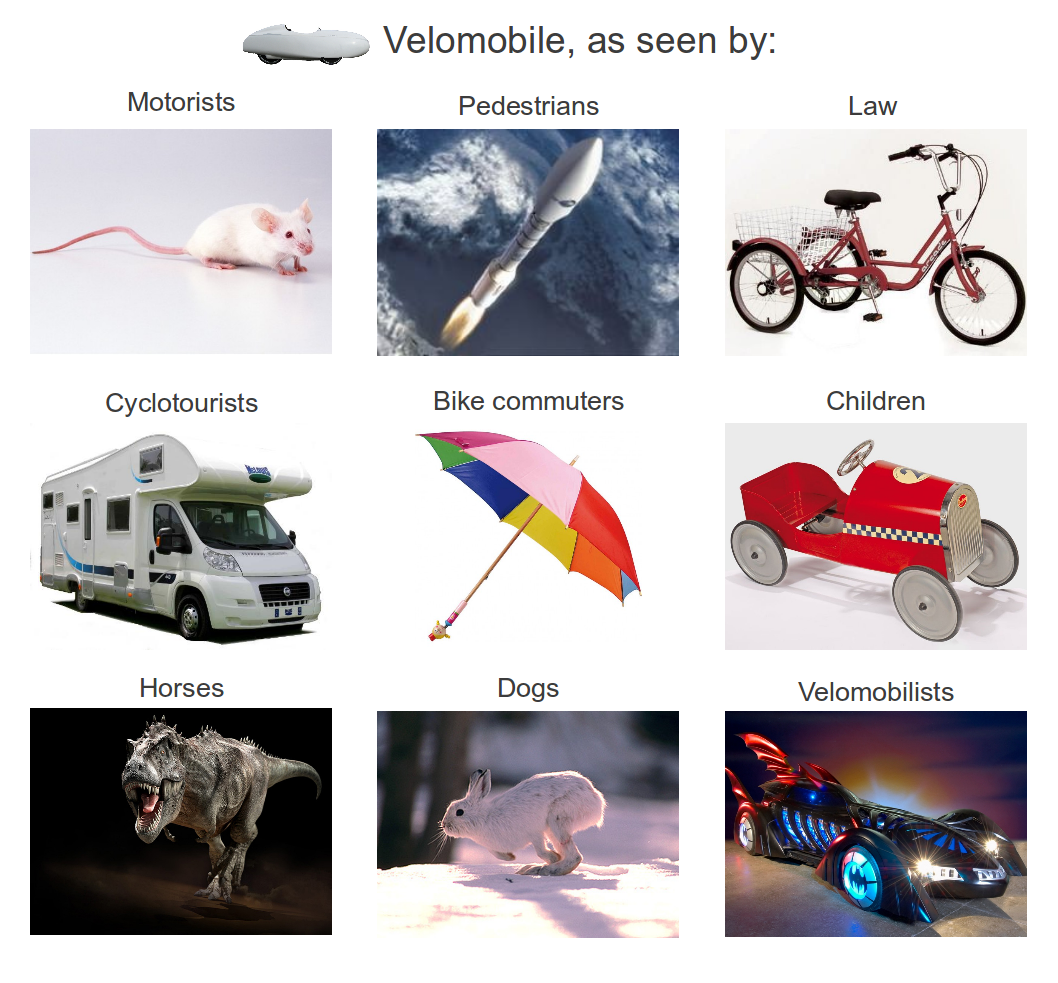

Recumbent bikes with bodywork evoke a curious effect. They look as fast as a racing car or a jet fighter, but of course, they’re not.

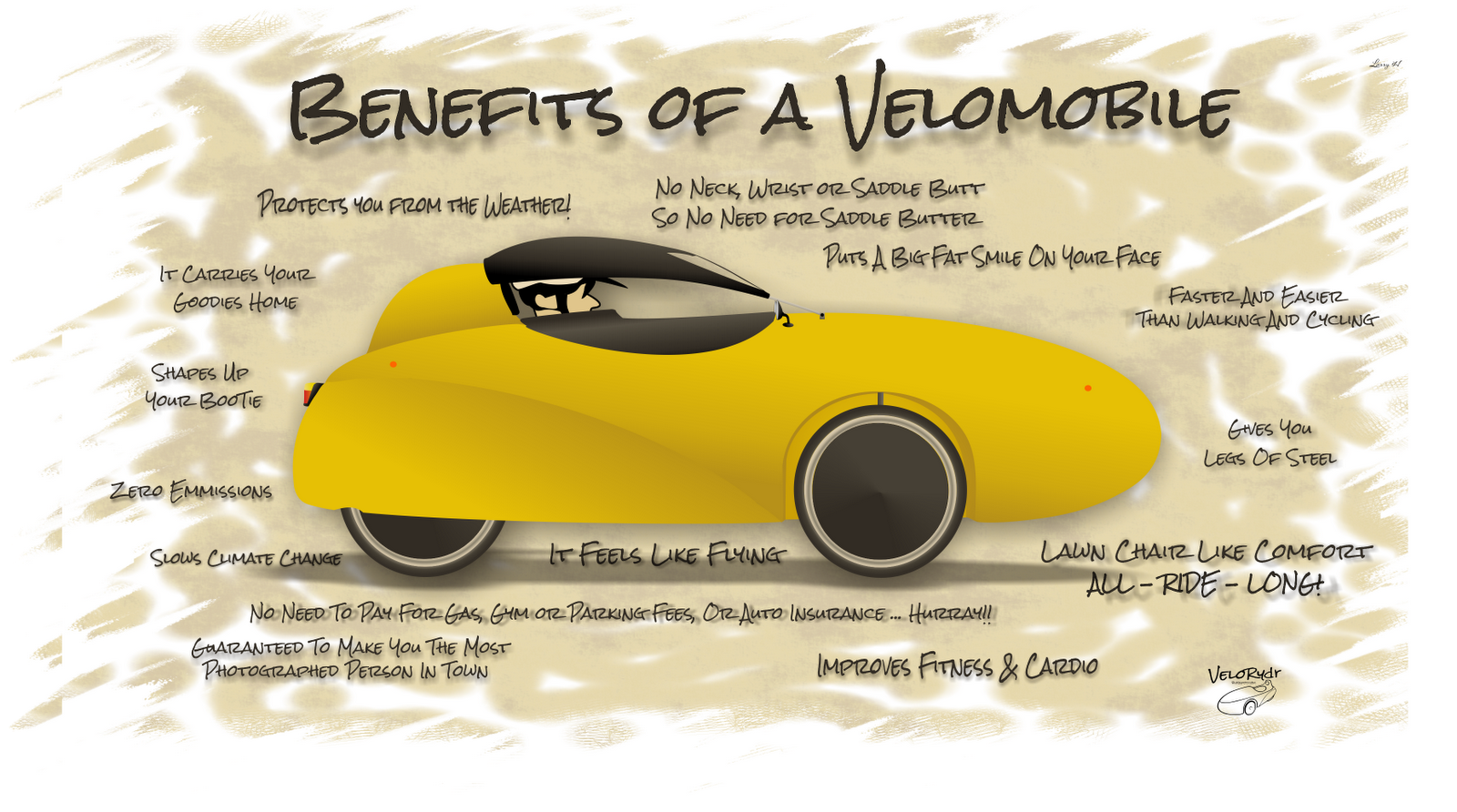

Nevertheless, thanks to the recumbent position, the minimal weight and the outstanding aerodynamics, pedalling a “velomobile” requires three to four times less energy than pedalling a normal bicycle.

This higher energy efficiency can be converted felt in terms of comfort, but can also be utilised to attain higher speeds and longer distances – regular cyclists can easily maintain a cruising speed of 40 km/h (25 mph) or more. The velomobile thus becomes an excellent alternative to the automobile for medium distances, especially in bad weather.

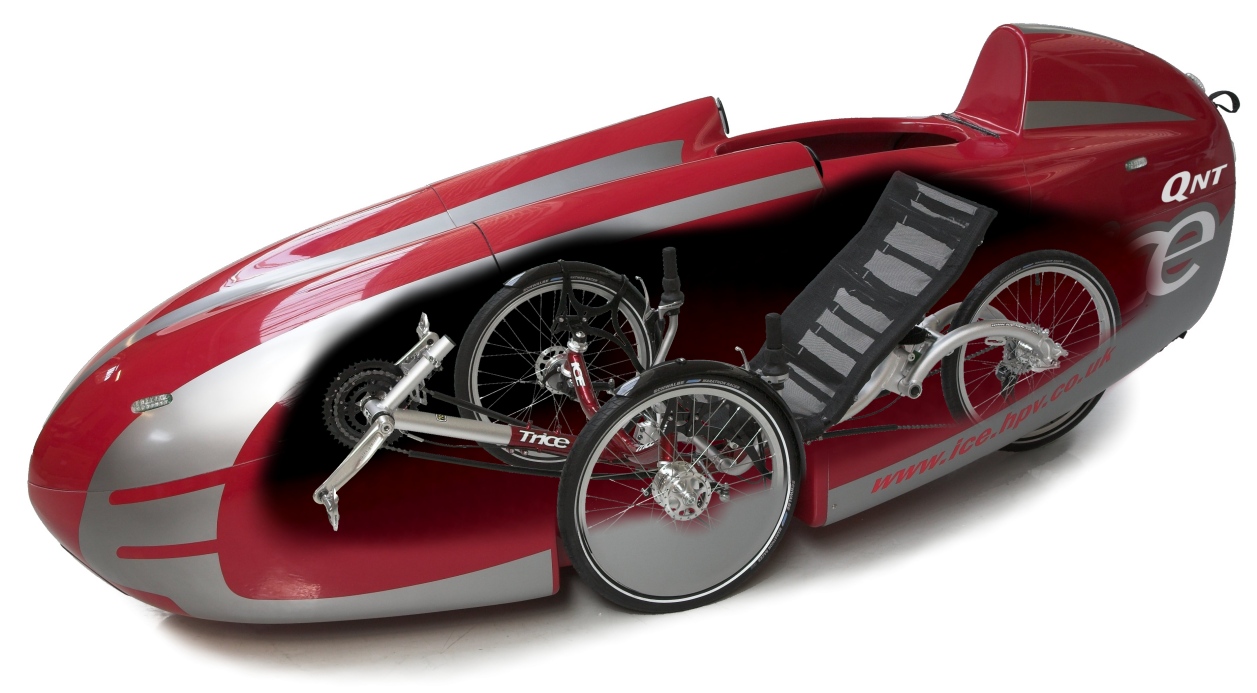

Basically, a velomobile is a recumbent bike with the addition of a bodywork. Recumbent bikes are considered a bit weird, but they have some interesting advantages over normal bicycles. For example, a recumbent bike has no saddle but a comfortable seat with back support, so that you sit or lie more comfortably and can keep pedalling for longer. Because of their superior aerodynamic capabilities, pedalling on a recumbent takes less effort, allowing you to travel more quickly and further than on a normal bicycle. Recumbent bikes can have two, three or four wheels. Trikes (3 wheels) and quads (4 wheels) offer the additional benefit of stability.

Picture: the Scorpion.

A velomobile – almost always a trike – offers two extra advantages over normal recumbent tricycles. The bodywork protects the rider (and mechanical parts) from the weather, so that the vehicle can be used in any season or climate. Furthermore, the aerodynamic shape of the bodywork further improves the efficiency of the vehicle, with spectacular results.

Velomobile versus bicycle

From the table below (source.pdf) one can observe that the power output required to achieve a speed of 30 kilometres per hour (18.6 mph) in a state-of-the-art velomobile (the Quest) is only 79 watts, compared to 271 watts on a normal bicycle and 444 watts on a neglected bicycle. Pedalling at a speed of 30 km/h thus requires 3.5 times less energy with a velomobile than with a normal bicycle. Going flat out (a power output of 250 watts) gives you a speed of 29 km/h (18 mph) on a normal bicycle and 50 km/h (31 mph) on a velomobile.

Source: “The velomobile as a vehicle for more sustainable transportation” (pdf).

NASA rates the average long-term power output for a male adult at 75 watts, while fit individuals might easily sustain more than 100 watts for several hours, from 200 to 300 watts for one hour, and between 300 and 400 watts for at least 10 minutes. Lance Armstrong is said to have averaged between 475 and 500 watts for 38 minutes during an uphill climb in the 2001 Tour de France. (Source: The human powered home).

If you normally commute by bicycle, you can do two things with a velomobile: Retain the same speed as you normally do, but use 3.5 times less energy, or arrive at your destination twice as quickly with the same effort. This high efficiency greatly enlarges the range of a pedal powered vehicle. The bicycle is generally being viewed as a transport means for short distances, mostly below 5 kilometres or 3 miles (= cycling 15 minutes at a speed of 20km/h or 12.4 mph). However, the average distance of a car trip in Europe and in the US amounts to between 13 and 15 kilometres (8 and 9.3 miles).

Picture: the Sinner Mango Red Edition.

A velomobile reaches a constant cruising speed of 35 km/h (21.7 mph) with the same energy output, so that the distance covered in 15 minutes becomes 9 kilometres (5.5 miles) instead of 5 kilometres (3 miles). At a speed of 45 km/h (not unusual for a regular cyclist) the distance covered in 15 minutes becomes more than 11 kilometres (6.8 miles). Thus, twenty minutes of pedalling on a velomobile sufficiently covers an average automobile trip. The velomobile could replace a substantial portion of car miles, especially because the vehicles also protect their occupants from wind, rain and cold.

Picture: the Quest.

By definition, velomobiles are built for speed. The bodywork offers a distinct advantage at higher speeds, starting at 20 to 25 km/h (12.4 to 15.5 mph). Above those speeds, almost all energy produced by a cyclist is channelled toward combating air resistance. Because of the upright position, the aerodynamics of a cyclist on a normal bicycle are disappointing. A velomobile, on the other hand, suffers less air resistance than even the most aerodynamic sports car.

At lower speeds, however, the relatively heavy (25 to 40 kilograms) velomobile becomes a disadvantage. It accelerates slower than a normal bicycle, and has considerably more difficulty climbing a hill. An electric assist motor can solve this problem in hilly regions. The motor can help the velomobile climb, while energy can be recovered from the brakes during the descent. Of course, an electric assist can also be considered on flat terrain, an option that is gaining a lot of popularity these days.

Picture: the Leiba x-stream.

By definition, the velomobile is essentially built for longer distances. For shorter city trips the traditional bicycle is unbeatable. It accelerates faster, it is more manoeuvrable, and it is very easy to hop on and off.

Velomobile versus electric car

Dries Callebaut and Brecht Vandeputte, the Belgian designers of the WAW-velomobile, calculated how the efficiency of a velomobile relates to the efficiency of an electric automobile (using their own data and this source). During an eco-marathon earlier this year they equipped their velomobile with an electric motor, a complete substitution for pedal power. This is not really what the vehicle is intended for, but the advantage of the experiment is that it allows for an unequivocal comparison.

The energy consumption of the WAW was measured at 0.7 kWh per 100 kms (62 miles). This makes the velomobile in excess of 20 times more efficient than electric cars currently on the market. For example, the Nissan Leaf requires 15 kWh per 100 kms. The enormous difference is of course due to the enormous difference in weight. Without the battery, the Nissan weighs just over a ton, while the WAW weighs less than 30 kgs.

Picture: the Versatile.

For a human powered velomobile the comparison is a bit more complicated and open to interpretation, because a human does not run (primarily) on electricity, but on biomass. The efficiency of a human powered velomobile thus depends on what the cyclist eats (the efficiency of an electric car also depends on how the electricity is generated). Callebaut and Vandeputte set the primary energy use to 0.6 kWh/100 km for a vegetarian diet from your own garden, to 2.4 kWh per 100 km for the average diet of the western non-vegetarian.

Picture: the Versatile.

A human powered velomobile is thus 15 to 62 times more energy efficient than a Nissan Leaf. Not just 6 to 25 times, because we are comparing primary energy here. The 15 kWh that is consumed by the Nissan equates to around 37.5 kWh primary energy since electricity plants (in Europe) have an efficiency of 40 percent.

You can also argue that burning fat is a positive thing regardless of where food comes from, since obesity and a lack of exercise are endemic throughout the western world. The energy that is now being wasted in fitness centres, or the fat that is hanging in front of the television, could be put to good use as an oil substitute in transportation. In this view, the velomobile consumes (just as the cyclist and the pedestrian) 0,00 kWh per 100 kilometres.

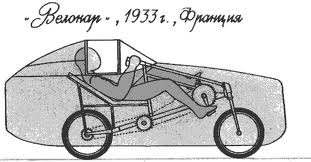

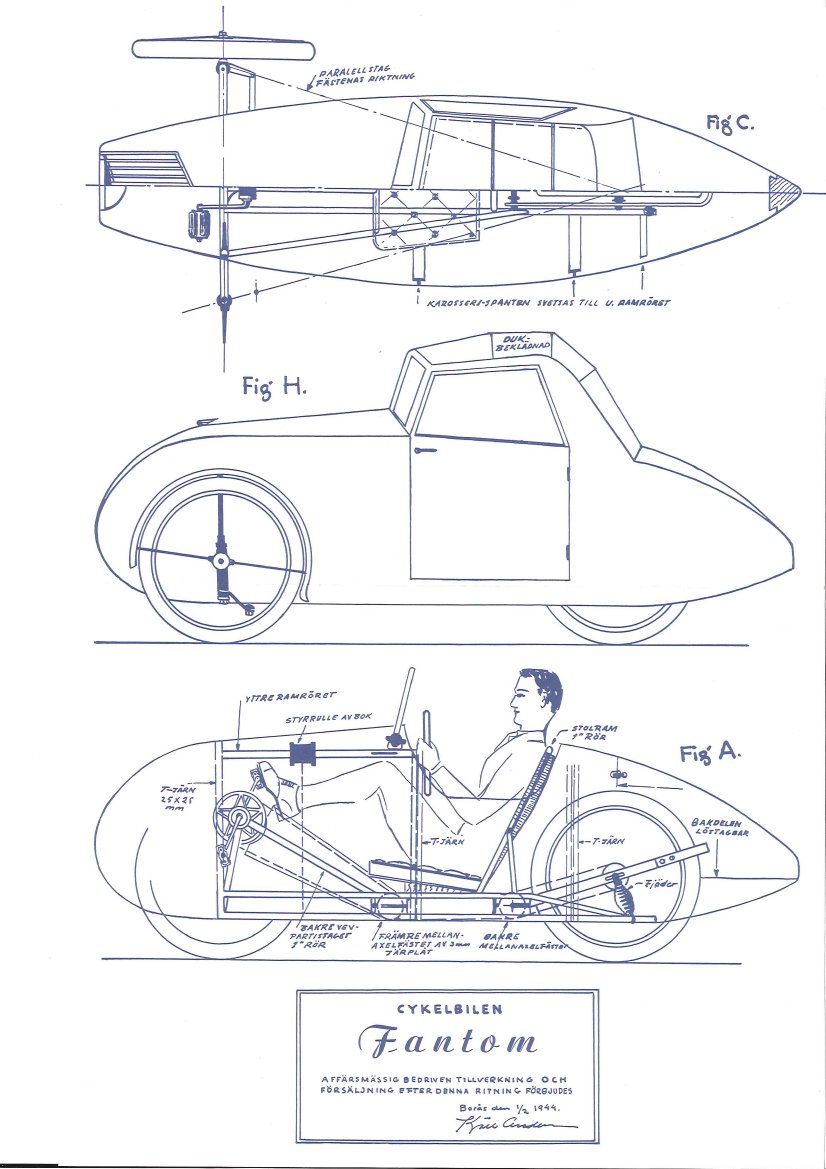

Origins

The origins of the velomobile can be traced back to the beginnings of the twentieth century, but the modern, streamlined velomobile only appeared in the 1980s. The first commercially available velomobile was the Danish Leitra. In 1993, the Dutch Alleweder appeared on the market. About 500 of them were were sold in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany throughout the 1990s.

Picture: the Alleweder.

The Alleweder introduced an important technological innovation: the self-supporting, monocoque coach work, similar in construction to that of a car – though much lighter. This gave the velomobile a sturdier construction without weighing it down. The suspension system introduced by the Alleweder was also inspired by automobiles. The bodywork of the original Alleweder is made from aluminum plates riveted together, a technique inspired by airplane builders.

With or without a roof

All velomobiles produced since then are based on the construction principles of the Alleweder. The only difference is that the bodywork no longer consists of aluminum but is made up of composites (like Kevlar). These materials are more expensive, but offer more freedom in designing the fairing, allowing for better aerodynamics.

Picture: the Go One 3.

A modern velomobile weighs between 24 and 40 kilograms, is about 250 centimetres long, 80 centimetres wide and 95 centimetres high. The three wheels have suspension and the bodywork has integrated rear view mirrors, head lights, indicators and (sometimes) brake lights. A velomobile also has a luggage compartment comparable to that of a sports car.

The present-day velomobile comes in two varieties: vehicles in which the head of the driver sticks out (like the Quest, the WAW, the Versatile, the Mango, the Velayo, and the Alleweder) and vehicles in which the driver is fully enclosed (like the Go-One, the Leiba, the Leitra, the Pannonrider and the Cab-Bike). In the case of a fully enclosed vehicle, part of the bodywork can be opened to get in and out. In a half-open velomobile, the driver enters and leaves via the hole where the head sticks through.

Velomobiles can have open or closed wheel arches. Closed wheel arches give better aerodynamics but they make the turning cycle larger and hamper the changing of a tyre.

Picture: the Pannonrider (picture credit) has solar panels on the bodywork (wind power is another option!).

Fully enclosed velomobiles give the best protection against bad weather, of course, but they do carry a few disadvantages. The main problem has to do with ventilation. Even in cold weather, the driver may “overheat”. A body that delivers 200 watts, produces around 1000 watts of waste heat, which mostly escapes via the head. In a fully enclosed velomobile hearing and sight are also affected. The windshield can steam up or it can become opaque because of rain or snow (windscreen wipers are not an option on any velomobile, probably because of the extra weight that would be added by motor and battery).

Picture: the Velayo.

A fully enclosed velomobile thus needs an efficient natural ventilation system (which can happen via air intake in the nose of the vehicle). Some manufacturers have come up with a compromise. The WAW has a small optional roof with a ventilation system that can be manipulated from the inside of the vehicle. It can be quickly installed and it fits in the trunk when folded up. The Versatile also has a smart roof, bypassing the heat and ventilation problem while still protecting the rider from the rain.

Picture: the Hase Klimax.

The German manufacturer Hase recently presented a recumbent tricycle with a foldable fairing (and an electric assist motor). This is not a compromise between a fully or a semi-enclosed velomobile but between the latter and a normal recumbent trike – the most comfortable and aerodynamic option in warm weather.

Two-seaters

Recently, some two-seater velomobiles have appeared, such as the Bakmobiel (a cargo bike) and the DuoQuest. The essential idea is that occupants sit next to each other. It’s good to see that cosiness still beats aerodynamics.

Another recent trend are velomobiles that have been especially designed to easily hop in and out of. The adapted design lowers weather protection and aerodynamics, but the result is still a more efficient bicycle at higher speeds, which comes in handy for shorter distances.

Are velomobiles too expensive?

The high purchase price is often mentioned as one of the largest obstacles for a breakthrough of the velomobile in the mainstream market. A fully equipped machine will cost you at least 5,000 euro (6,700 dollar) – considerably more than what you pay for a good quality bicycle. In the US prices have come down from a level twice as high, since now some of the popular Northern European brands are also produced in the States. Shipping a velomobile across the Atlantic is not cheap.

Picture: the Quest.

The high price stems partly from the surcharge of a recumbent, but mainly from bodywork. Each velomobile is hand-crafted, with the fairing requiring the most work. It would of course be cheaper to produce velomobiles on an assembly line, especially when this would happen in a low-wage country. But even then – including social exploitation and extra environmental costs – nobody expects to see a velomobile sold for less than half the current price. Lightweight materials, crucial to make the technology work, just happen to be expensive.

Picture: the Quest.

You can look at it differently, of course. A velomobile is more expensive than a bicycle, but it is cheaper than an automobile. Since the performance and the comfort are also in between that of a car and a bicycle, the price starts to look more reasonable. Moreover, a car requires fuel, and a velomobile doesn’t. Maintenance is limited to changing the tyres. Whoever changes his or her automobile for a velomobile is definitely making a economical decision. Governments could help overcome the purchase price by financially supporting velomobiles instead of electric cars and biofuels – at least their ecological gain is clear and they don’t need a completely new charging infrastructure.

Alternative to the automobile?

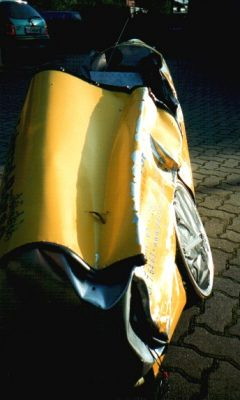

The most important obstacle for the velomobile is not the purchase price. It is the competition of the automobile. Although a velomobile can ride on a wide enough bicycle path, because of its larger dimension and higher speeds the vehicle is more suited for the road. The concept of the velomobile is sound as long as the vehicle does not have to share the road with automobiles. On current roads, piloting a velomobile would be relatively dangerous. Car drivers don’t always see you, and in spite of the many strengthenings in the bodywork you are very vulnerable against, say, a Jeep Cherokee.

Picture: the Alleweder.

A breakthrough in the velomobile thus requires either a completely new infrastructure for pedal power, or the substitution of velomobiles (and other human powered vehicles) for automobiles on the existing local and regional road system. The latter option, which I prefer, would not be conducive to car sales, but there is nothing or nobody that stops car manufacturers from producing velomobiles.

© Kris De Decker (edited by Shameez Joubert)

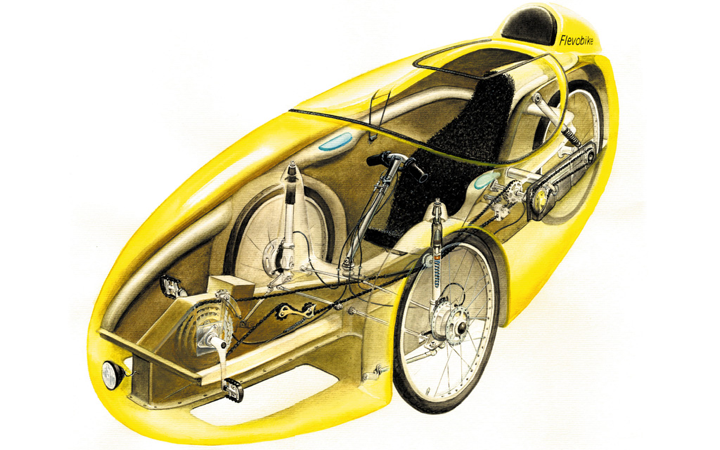

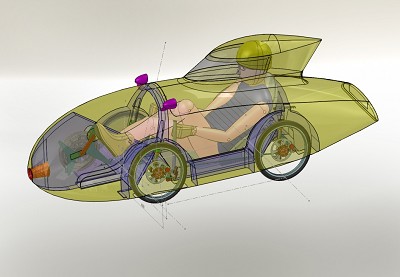

However for most velomobiles this is not possible, as the fibres in the Fibre Reinforced Plastic (FRP) body, render the material opaque. So in the physical world, apart from what can be seen through the canopy, all else is destined to remain a mystery. Leaving the physical world and turning to the illustrated and virtual worlds there is no such limitation, here artists, photo-manipulators and computer modellers are free to render what ever surface they like transparent.

However for most velomobiles this is not possible, as the fibres in the Fibre Reinforced Plastic (FRP) body, render the material opaque. So in the physical world, apart from what can be seen through the canopy, all else is destined to remain a mystery. Leaving the physical world and turning to the illustrated and virtual worlds there is no such limitation, here artists, photo-manipulators and computer modellers are free to render what ever surface they like transparent.